Restoring Hazelwood by removing invasive species

Coillte Nature is restoring an ancient alluvial woodland in Co. Sligo by removing the invasive species that are slowly choking it. We've made a short video to show you how we're tackling the problem and what the benefits will be, and explain it all in greater detail in the blog below.

Close to Hazelwood’s recreational forest is a rare and precious alluvial woodland

At the National Biodiversity Conference in 2019, we announced a plan to restore Hazelwood forest’s alluvial woodlands as one of the conference’s 40 ‘Seeds for Nature’.

Hazelwood is best known for its popular recreational forest, which lies on the shores of Lough Gill and overlooks Yeats’ famous Lake Isle of Inisfree. It’s a mature mixed woodland featuring a wide variety of non-native conifer and broadleaf species, as well as some areas dominated by native species. Being only 5km from the town centre, it’s very popular with the people of Sligo, who make fantastic use of the beautiful forest on their doorstep.

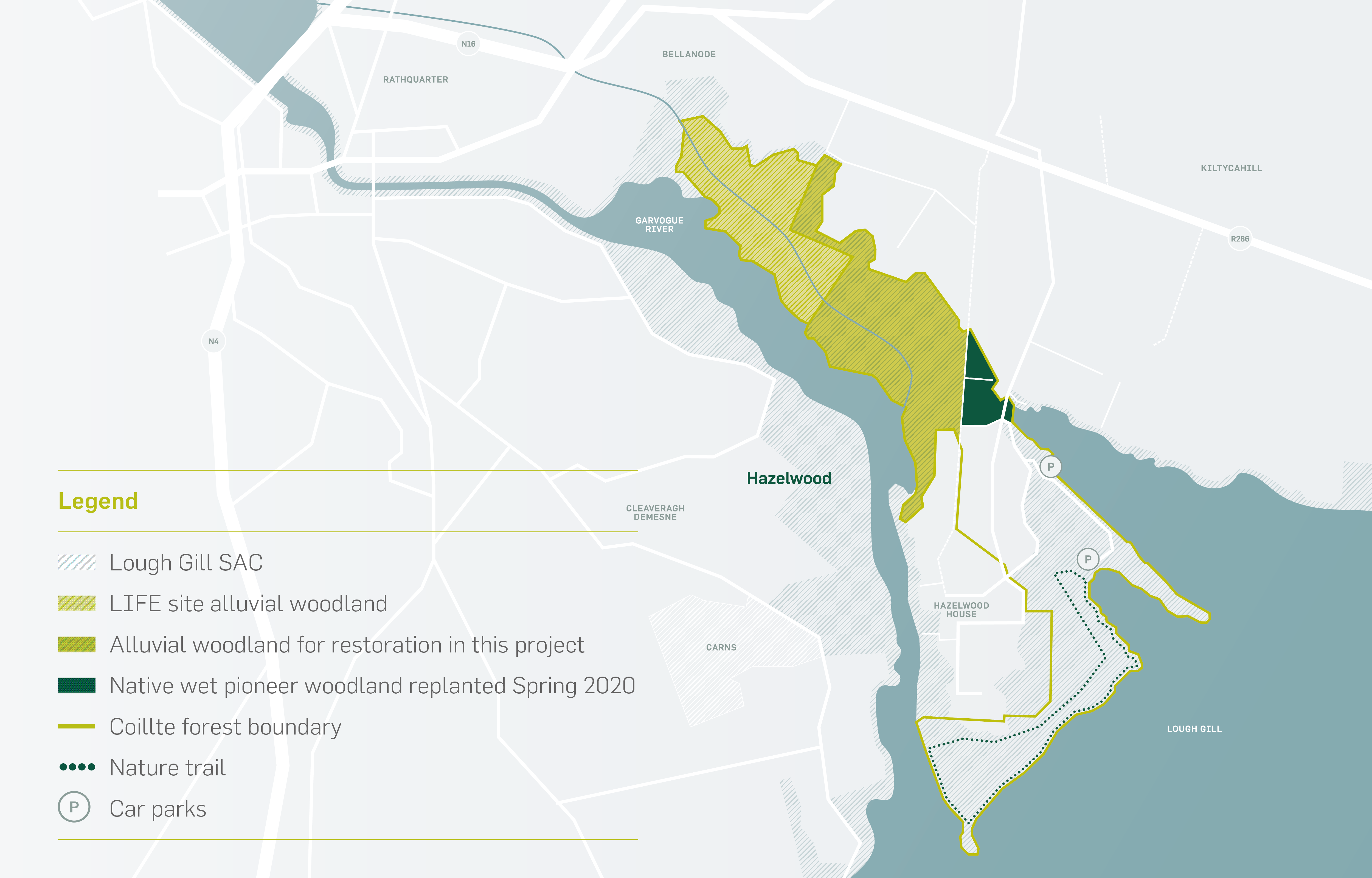

But not everyone knows that tucked away to the north of the main recreational forest, along the banks of the Garvoge river, is one of the rarest and most precious woodland habitats in Ireland - a very special native alluvial woodland.

Endangered birds, mammals and plants live here

Alluvial woodlands occur in areas that are subject to periodic flooding where the soil becomes saturated, especially in winter. The trees that grow naturally here include birch, willow, alder, ash and oak. In drier areas, you’ll find hazel, bird cherry and buckthorn too. The woodland floor is home to reeds, marsh marigold, flag Iris, marsh cinquefoil, marsh bedstraw, purple loosestrife, skullcap, meadowsweet and gipsywort, as well as Red Listed species like bird’s nest orchid, yellow bird’s-nest and ivy broomrape.

Red squirrels, pine martens, otters and badgers make their homes here, as do birds of conservation concern, such as kingfisher, sparrowhawk and woodcock. Salmon and sea trout lurk in the woodland feeder streams where ample cover is provided under a tangled canopy of trees and shrubs. Hazelwood’s alluvial woodland is among the finest examples of this rare habitat type in the country and as such is of very high ecological significance. It is a Special Area of Conservation (Annex 1 Priority Habitat). Because it was present on our oldest 1830 Ordnance Survey maps, it is classified as ‘Old Woodland’ and some is almost certainly even older ‘Ancient’ woodland.

Unless we take action, the woodland will die

However, parts of this habitat are currently plagued by dense thickets of rhododendron and Cherry laurel. These invasive shrubs cast a dense shade on the understorey, which obliterates the ground flora and prevents natural regeneration of the woodland. Leave it like this for too long, and the woodland will die.

Between 2005 and 2009, 26 hectares of Hazelwood’s alluvial woodland was restored under an EU LIFE project, improving its conservation status significantly. But there’s more to do! That's why we are restoring an additional 30 hectares to improve the status of the entire alluvial woodland even further.

Restoring Hazelwood is challenging work

Work got underway this year on clearing the jungle of invasive species that had taken over. As the photos and video (above) show, it’s not an easy task. The worst of the rhododendron and Cherry laurel thickets are up to 8m tall and extremely dense.

Forest workers with chainsaws and brushcutters cut down the invasive plants branch by branch and feed them into the chipping machine. Every branch of rhododendron – even small stems – must be retrieved from the forest floor. Even the smallest part of the plant left behind can grow roots within a few weeks, potentially re-establishing itself and leading to further recolonisation.

Once an area has been felled and chipped, the stumps are treated with herbicide to kill them. Using herbicide in any habitat should only be done when absolutely necessary and with great caution, but in a Special Area of Conservation like Hazelwood’s alluvial forest, this is even more important, especially as it might be carried downstream with negative impacts.

Strict protocols exist in sensitive, wet habitats like these and we worked closely with the National Parks and Wildlife Service to figure out the safest and most effective way to tackle the infestation while protecting the habitat.

The approach that we agreed on was to use ‘eco plugs’: small, sealed pellets containing herbicide that can be used on the large- and medium-sized stumps that are over 10cm in diameter.

First, we use a specially adapted drill bit to drill exactly 3cm into the perimeter of the stump. The perimeter is the living part of the shrub and targeting it directly is the most effective way of killing it. Then, we insert the eco plugs into the holes, where they release the herbicide with no risk of spillage.

Drilling into the smaller stumps risks splitting the timber, making them even harder to treat. So instead of using eco plugs we wipe them with herbicide using a sponge with an attached feeder pipe (that many people will be familiar with from their own kitchen!). Again, this significantly reduces the risk of spillage.

Subsequently, if there is any localised regrowth of rhododendron and Cherry laurel it will be spot sprayed, strictly under suitable climatic conditions (no wind or rain).

But it will be worth it

The restoration works will likely take a number of years and will require regular follow-ups in the future to ensure that any re-growing invasive species are also removed and killed. But it’ll be worth it. Improving the health of Hazelwood’s alluvial woodlands will ensure that the wildlife living within this unique habitat can thrive and that the ecosystem is protected and more resilient, ensuring its rejuvenation and longevity.